Yes, yes, I know it’s out-of-date and I haven’t done it for ages.

The Back Story

For some years now, I’ve been looking at book titles published in New Zealand in any given year, broken down by the gender and ethnicity of authors. To start with (in 2008), I just looked at poetry titles by gender. I did this because I was curious to know what the proportions were (in 2008, 63% of titles were written by men; 36% by women and 1% other (co-authored by a man and a woman)).

Later, I started looking at ethnicity as well, also driven by curiosity: how level is the publishing playing field? Is it easier for Pākehā to get published compared to Māori, Pasifika, Asian and other authors? This matters to me because I like things to be fair and because I don’t want to just read stuff written by people like me. (For the record, I’m Pākehā, born in the UK, and I’ve lived in Aotearoa since I was twelve. My pronouns are she/her.)

Later still, I added fiction titles to the list, then non-fiction. I published the analysis on this blog over several years and hoped it might be useful in some way. I’ve been really pleased that my findings have been able to support calls for a more representative national literature, including Tina Makereti’s excellent talk, Poutokomanawa — The Heartpost (well worth a read), at the Auckland Writers Festival on 17 May 2017.

I didn’t repeat the analysis for 2016, 2017 or 2018. I had good intentions, but it takes days and days to do it and I was focusing on other things. However, last year I analysed the titles published in 2019 – but didn’t get around to blogging about it because life got in the way – so here at least is a comparison that can be made between 2015 and 2019, in case anyone is interested. I also have data for poetry titles for 2011, so I’ve added that into the mix. If I find the time to analyse the data for 2020 and/or 2021, I’ll blog about it later this year. (There’s always a delay, because the information I use is published months after the end of each calendar year.)

The Findings:

Poetry – Gender

With poetry, there was a switch in the gender balance between 2015 and 2019. In 2015, 56% of poetry titles published in New Zealand were written by men and 44% by women (slightly more balanced than the 58% men, 42% women in 2011) . In 2019, 56% of poetry titles were by women, 43% by men and 2% by a non-binary poet. (Sometimes the figures will not add to 100% due to rounding errors.)

So, all good if there are a few more blokes published in one year and a few more sheilas the next. Hopefully it will settle into an equal-ish sort of distribution. I don’t know what proportion of the population identify as non-binary, so I can’t comment on whether 2% (1 poet out of 61) is reasonably representative. But it’s a start and maybe we’ll have some data after the next census.

Poetry – Ethnicity

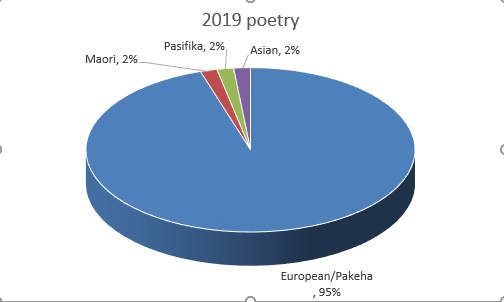

Ethnicity is a much sorrier story. Of poetry titles published in 2019, a full 95% (58 titles) were by Pākehā authors. Yep, leaving 2% each for Māori, Pasifika and Asian poets (ie 1 book each). To put it in context, around 17% of New Zealanders are Māori, around 15% are Asian and around 8% are Pasifika.

I honestly thought things would have got better. This is some serious under-representation in our national literature right here. I know some publishers have been making sterling efforts to address that – please keep going.

Here’s the miserable poetry pie chart that illustrates how things were in 2019. Pākehā poets were getting a whole lotta delicious poetry pie and 3 poets who weren’t Pākehā managed to get some crumbs. We poets are all very hungry for the pie and there’s less and less of it about, but this is a very sorry state of affairs.

Lani Wendt Young has written about the impact of the digital age (Lani Wendt Young on how the digital era is changing writing and reading for the better | RNZ) and maybe it’s the case that Māori and Pasifika poets are more drawn to digital media – it would be interesting to look at who is performing their poetry live or online and who is publishing on Instagram or other online media. But I’ve only looked at poetry on the page and it looks dismal.

Dwindling supply of poetry

In more general bad news for poets, it is harder to get a book published these days than it was in 2008, when I first looked at the poetry stats. In 2008, 88 poetry books were published; in 2019, it was 61. That’s a 31% drop over eleven years. Many thanks to all the wonderful publishers out there who continue to do this as a labour of love.

It’s possible some publications have been missed (I rely on the Journal of Commonwealth Literature for information) and there is also a healthy zine scene out there that I don’t include, but still. Is it just that everyone’s on Tik-Tok and Insta these days and there’s less demand for poetry you can hold in your hand?

Fiction – Gender

So, fiction’s got to be better, right?

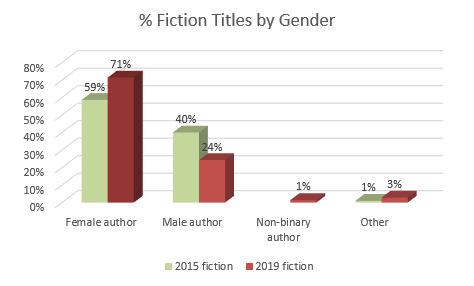

Well, the news is that the laydeez have taken over, leaping from 59% of titles in 2015 to 71% of titles in 2019. Which is – um – great in some ways – but I want to read stuff from the chaps as well. So, gentlemen, step up and get writing them novels, and publishers, please don’t discount a novel just because it’s written by a bloke 🙂 (If anyone’s wondering what ‘Other’ is in the graph, these are usually novels written by multiple authors who are different genders eg a novel co-authored by a man and a woman.)

Fiction – Ethnicity

Ethnicity stats for fiction have changed quite a bit between 2015 and 2019 too, in a good way. In 2015, 91% of fiction titles were by Pākehā authors, 4% each by Māori and Asian authors and only 1% by Pasifika authors. By 2019, 7% of titles were by Māori authors, 7% by Asian authors and 6% by Pasifika authors. This does not come close to reflecting the proportion of Māori, Pasika and Asian people in the population, but at least it’s heading in the right direction. In any case, I wouldn’t expect there to be an exact match because of the different population structures of different groups (the Pākehā population is skewed towards older age groups; Māori and Pasifika peoples have more youthful population structures).

The population structure of writers overall would be different again, skewed towards older age groups with fewer writers under 30. (And that’s okay because it takes time to learn our craft. I remain grateful that most of my early endeavours have not seen the light of day, although ‘Bonfire Night’ as published on the wall of my classroom when I was six remains a triumph. On reflection, however, I do feel that ‘rockets in the sky’ would have been a better line than ‘bangers in the sky’. But I digress.) In any case, these proportions may be slightly better than they look at first blush.

Overall, there were 75 fiction titles published in 2015, reducing to 70 in 2019. Not enough data to know if this is a trend.

Non-fiction

I included Letters and Auto/biography, but left out Criticism and Translations.

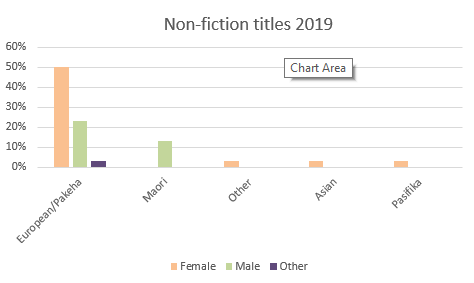

77% of authors were European/Pakeha; 13% were Maori; 3% were Asian, 3% Pasiifka and 3% other ethnicities. 60% of authors were female; 37% male and 3% other (one book was jointly edited by a man and a woman). So not too bad overall, although I’m surprised there were not more men writing non-fiction. In 2015, 62% of non-fiction writers were male; 38% female. Numbers are small, so maybe it fluctuates a bit year on year.

Conclusion

I don’t know. Maybe writers, especially young writers, are moving into more democratic forms of publishing – like self-publishing online. In the meantime, the distribution of pie may have improved in some respects, but it’s still looking pretty skewed, especially in the poetry world.

Methodology

I make no claim to have conducted proper research. I have performed a quick and dirty analysis of titles listed in the Journal of Commonwealth Literature, which publishes an annual round-up of titles published in Commonwealth countries in the previous year. It’s accessible online for a fee. Then I try to find out how each author defines themselves in terms of gender and ethnicity. I usually look at three or more websites (eg author pages on publisher sites, Wikipedia, writers’ websites, the Academy of New Zealand Literature, the NZ Society of Authors). If someone mentions their pronouns or ethnic background, then great, I use that. Gender is usually fairly easy to find, although if someone has changed their gender identity since publication. I may not have picked it up and they may be sitting in the wrong category.

Ethnicity can be trickier to find. If I’ve looked at several sites and there is no mention of ethnicity, I assume the author to be Pākehā. I may miss a few people this way. For books written by multiple authors with different genders and /or ethnicities (eg if a Pākehā man and an Asian woman co-authored a book), I list them as Other. If someone mentions they have a parent who is Māori, Pasifika or Asian, I add the person to the respective group. It’s not perfect, but it does allow me to look at trends over time.

If anyone finds errors, please let me know. I do my best, but this stuff is not peer reviewed.

Other Reading

Tina Makereti’s speech/essay Poutokomanawa – The Heartpost – Academy of New Zealand Literature (anzliterature.com)

Michalia Arathimos’ essay: The wharenui of New Zealand literature remains a gated community – E-Tangata

Tusiata Avia, Vaughan Rapatahana, Maria McMillan and Sarah Jane Barnett Why Can’t We All Just Get Along? The Literature Edition – Pantograph Punch (pantograph-punch.com)

Lani Wendt Young Lani Wendt Young on how the digital era is changing writing and reading for the better | RNZ

My previous blog posts on this:

[…] Who Gets Published in Aotearoa? – the 2019 round-up New Zealand Fiction & Non-Fiction by Gender & Ethnicity 2015 NZ Poetry 2015 by gender & ethnicity NZ Fiction & Non-fiction by gender & ethnicity 2014 Poetry published in New Zealand, by gender & ethnicity – to 2014 Poetry & Gender in New Zealand Publishing – an occasional series Poetry & Gender in New Zealand Publishing Part 2 […]